Our Special Interest group event at CHI 2019, titled “Evaluating Technologies with and for Disabled Children” was very well attended. Between 30 and 40 participants were motivated enough to come at 9am on the last day of the conference! We learned a lot from this encounter (including on SIGs’ structure), and summarise some of the discussions, as well as follow-up actions. We built a mailing list of all participants, open to new subscriptions.

Practical difficulties when conducting evaluations with disabled children

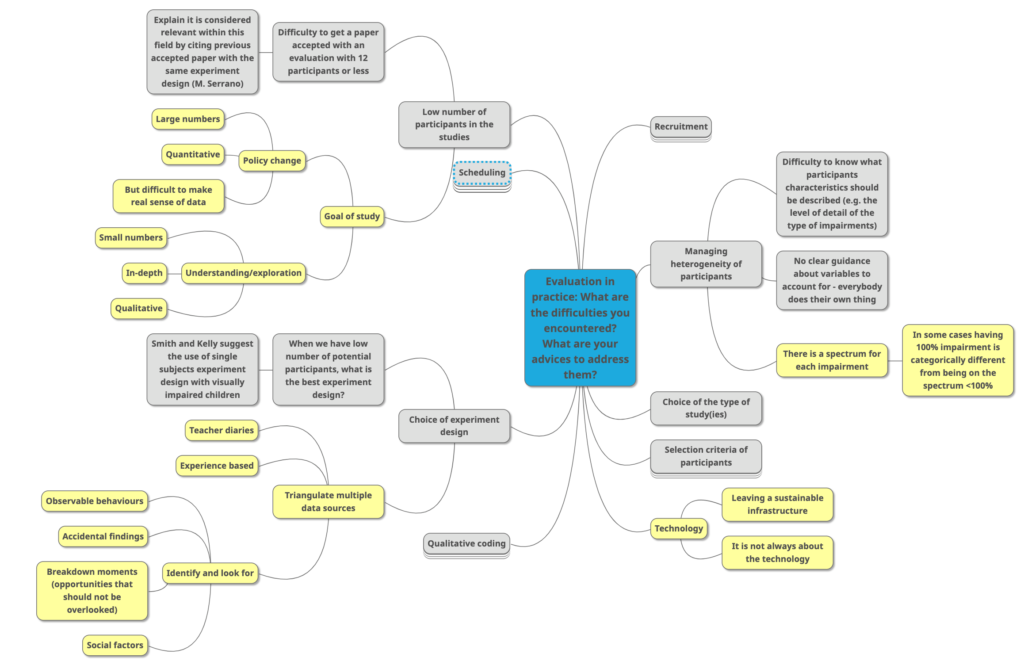

What makes a good qualitative evaluation? How to answer to reviewers who think there should be more participants in the study, even though there are very few people with this type of impairments? What are the experiment design accepted in this field of research? We are mindmapping questions and advices collaboratively. Are you new to this field and have questions? Do you have advices to give?

The key points that we have discussed as summarized in the mind map are:

Challenges:

- For most impairments there is a spectrum of the level of impairment and for some, having 100% impairment is categorically different from being on the rest of the impairment spectrum (100% visual impairment is very different from partial impairment), yet in many cases they are treated as if they are the same;

- We should be focusing on how we can leave a sustainable technology infrastructure for the technology to be used after the research study.

Suggestions:

- When it comes to data collection, best practice is triangulating different sources, such as teacher diaries and observations;

- Identify the relevant observable behaviours and look for those;

- Pay attention to: Accidental findings; Breakdown moments – these are valuable opportunities that must not be overlooked

- When it comes to number of participants, the discussion and general consensus was that unless the research is to drive policy change, a small, in-depth qualitative study is the best way to gain deep understanding to answer the research questions.

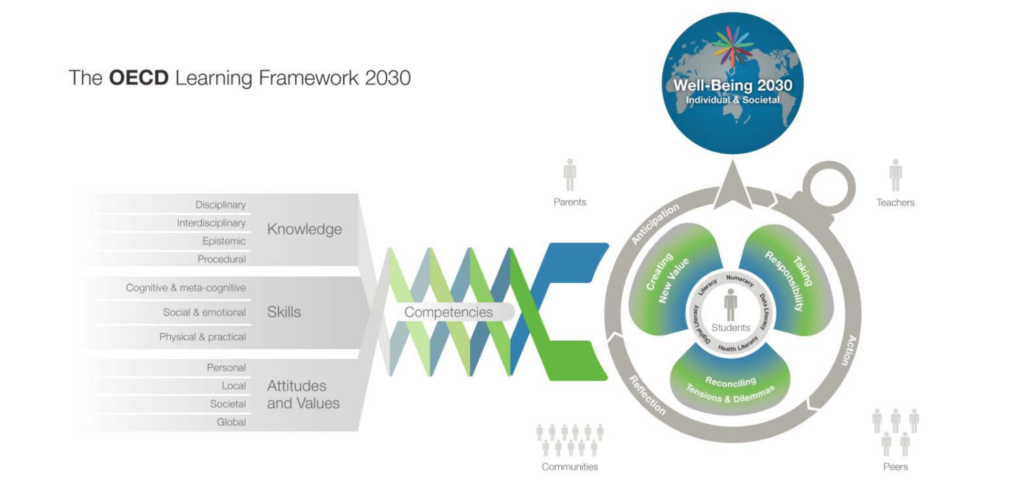

The OECD Learning Framework 2030

The OECD Learning Framework 2030 identifies individual and community well-being as the main goals of education. How should HCI account for these new goals? What new criteria for evaluating the success of a technology should we use?

First thing we noted is that the researchers present at the table were not familiar with this OECD framework. Hence we discussed the extent to which other stakeholders that we typically engage with (e.g. funding agency, local government services, schools) are familiar with and influenced by this framework.

We then engaged in attempting to understand and critique the various aspects of this schematic, in particular how the components and dynamics represented in the schematic would change if we take the perspective of disability as a driver for thinking about learning technologies and evaluation.

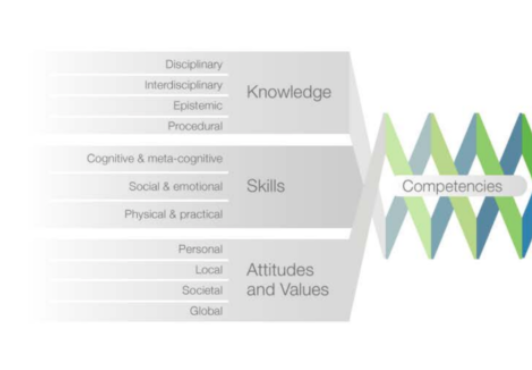

We found that the left hand side of the schematics, i.e. the breaking down of education and learning in terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes and values could be a helpful way of thinking about different target areas for evaluation. They could act almost as a list of evaluation areas and criteria. However, we also agreed that some of these components seem to place too much emphasis on learning as knowledge acquisition and ignore other experiential and social aspects of learning. Moreover, it also ignored other more informal ways of learning and of seeking knowledge.

For the right hand side of the schematic, we agreed that the separation of agents could lead to thinking about learning technologies into terms that are likely to emphasise separation and isolation. It might not be helpful in considering more holistic views of interactions between these various actors. We also considered how moving different actors into the centre of the set of priorities is likely to change the dynamics between them and therefore the framework as a whole. For instance, what happens when technologies place emphasis on the teachers vs emphasis on the peers or the parents. We also considered the missing complexity of dealing with disabilities across these actors: the design and evaluation of technologies change when parents or teachers are disabled and not necessary the students only. So, in this sense our thinking about evaluations should be considering both moving different actors into the centre, including multiple actors at the same time, and considering disability across a wider range of actors and a wider range of disabilities. This would result in a much more complex and richer picture of the challenges at hand, which is not captured by this framework.

Finally, we noted the extent to which this kind of framework is applicable across the diversity of contexts researchers face. The framework reflects a western interpretation and vision for the future of learning. It might not be readily application to societies in the Global South who have yet even more diverse and richer conceptions of learning, of disability, and of interactions between the various actors depicted in the OECD framework.

Taxonomy of evaluation methods in this field

There are no reviews of the type(s) of evaluation for inclusive educational technologies in HCI. How should we go about conducting this? What are the criteria you want to see in a literature review? Should we develop taxonomies of these technologies to simplify the design, evaluation and review process? What should be the level of granularity of systematic reviews?

To address these questions, we had developed lists of issues and elements that could be important when assessing evaluations in this field, from discussions regarding evaluation during our earlier workshop, and the finding that very few proposed assistive technologies have been thoroughly evaluated, which compromises their uptake and impact on education.

During preparations, we had started by separating experimental and quantitative approaches from qualitative evaluations and mixed-methods evaluations. The aims of these evaluations differ, and the technologies evaluated probably also differ.

A few takeaways from this discussion:

- There seems to be a fairly strong agreement that in a HCI paper, the more the prototype is innovative, the less evaluation matters (in the first article on a project anyway). When technology comes near deployment stage, evaluation becomes more of a matter for education sciences. This might contribute to explain the lack of evaluation in this domain: if partnerships are not in place with educational sciences researchers or practitioners from the beginning, what happens to our prototypes?

- When reviewing quantitative, experimental evaluations, critically discussing who counts as participants and the factors that were not included in the evaluation was deemed crucial. As advocated by Kelly and Smith, single subjects experiments could be used more widely in HCI;

- For qualitative approaches to evaluation, one participant, Seray Ibrahim, calls for innovative means of representing the literature. Specifically, she argued for timelines demonstrating how design and review processes are entangled, and the development of evaluation criteria over time (for instance, if you start with an evaluation based on standard exams but notice it would be better to evaluate impact on collaboration). This would enable researchers to better situate the stage they are at and compare it to other projects;

- Which leads to example case-studies: although there are a few papers about adapted evaluation frameworks, it might be better given the diversity within participants abilities and educational goals, to function like rehabilitation practitioners and publish more well-framed case studies of a given technology. When case studies converge regarding the benefits and pitfalls of a given technology, it leads to new ‘best practices.’ This requires to have venues accepting replication studies!

- Finally, one unresolved issue is how to support the adoption of innovative evaluation methods, while still maintaining coherence in the field.

Overall, this discussion highlighted the need for further community effort on setting and sharing standards for evaluation of technologies with disabled children, a concern shared by the Interaction Design for Children community .

Critical perspectives on evaluation

The discussions at this table, facilitated by Katta Spiel, focused on the articulation between individuals and community, opening questions or keeping them open. Participants in the SIG were interested in power structures and imbalances that are core to working not only as adult researchers with children, but also around the notion of disability related experiences whether they are shared, similar, differently or non-existent on researchers’ side. In thinking through our practices in evaluating technologies with disabled children we were interested in epistemological questions on which knowledge is attended to and seen as valid and how we might include alternative ways of knowing as well as a critical lens in making space for previously underrepresented perspectives. We then shared our experiences and practices and the issues we encountered along to understand which might be useful in understanding those dynamics more generally.

As a preliminary result, our conversations brought up more questions for the future which might be helpful to further methodologically strengthen evaluation processes with disabled children. Among them: How do we integrate disability justice to evaluation protocols? Is participation enough? How could institutional ethics boards better represent the disability community and understand its challenges? How to foster accountability and to whom?